When you write, you’re selling something: A story. A belief system. A product.

UX writing is no different.

Your marketing copy sells your product. Your UX writing continues selling it.

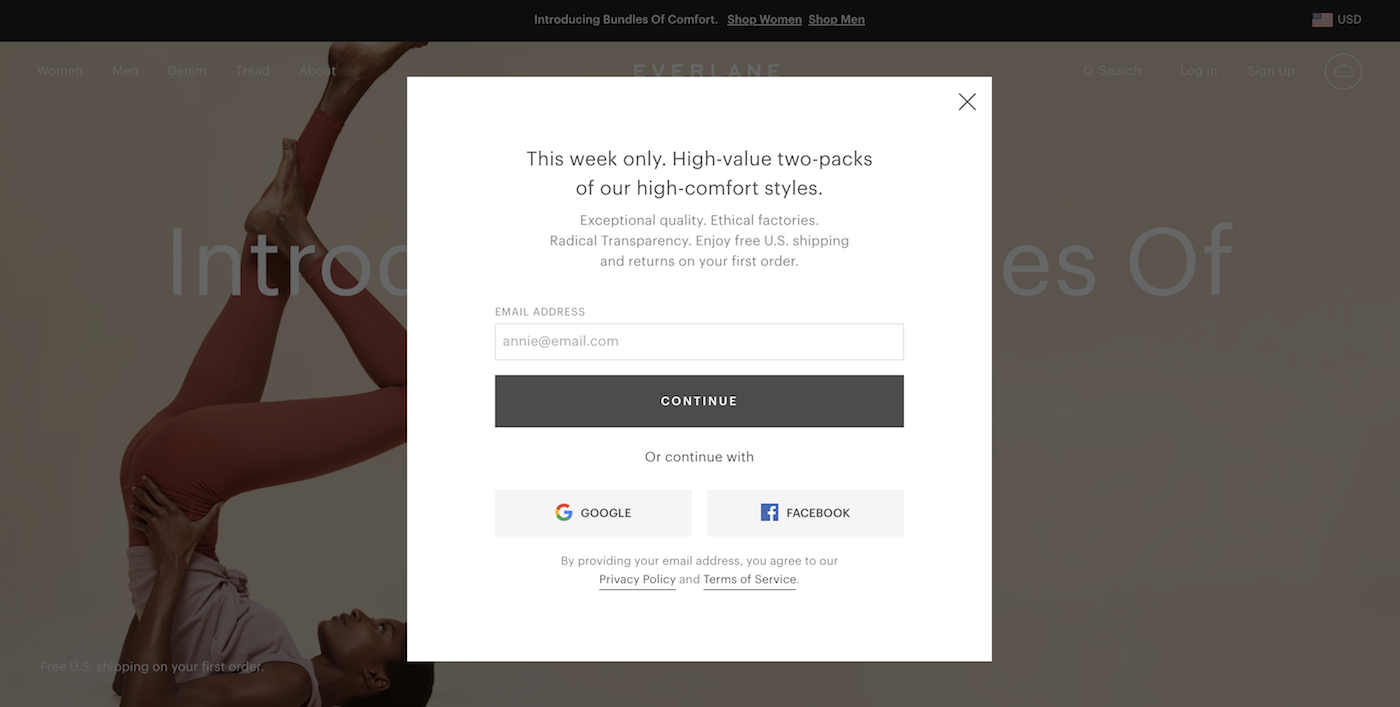

Good UX copy affirms our decision to buy your product. It makes it enjoyable and satisfying to use, ensuring we keep using and paying for it. We then become walking advertisements every time we tweet about your product or recommend it to a friend.

And so, the same writing principles you'd apply to advertising or marketing can be valuable here.

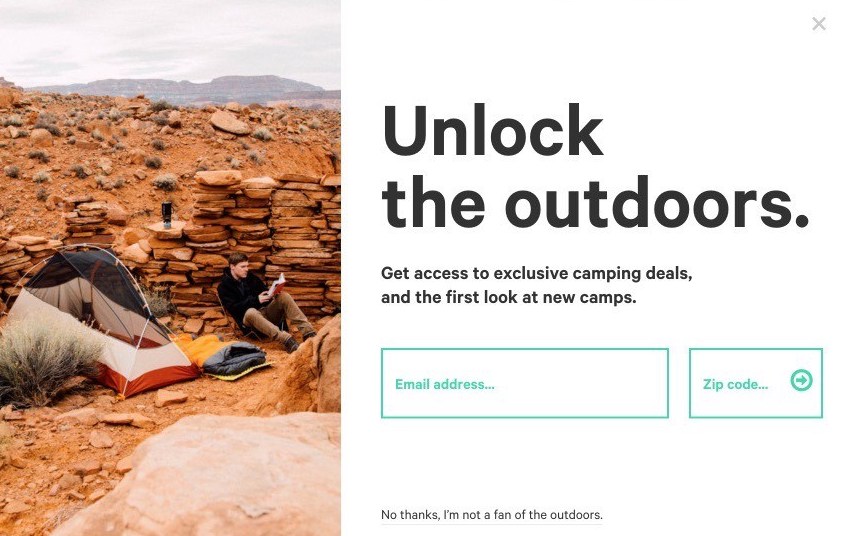

Don’t stand in our way.

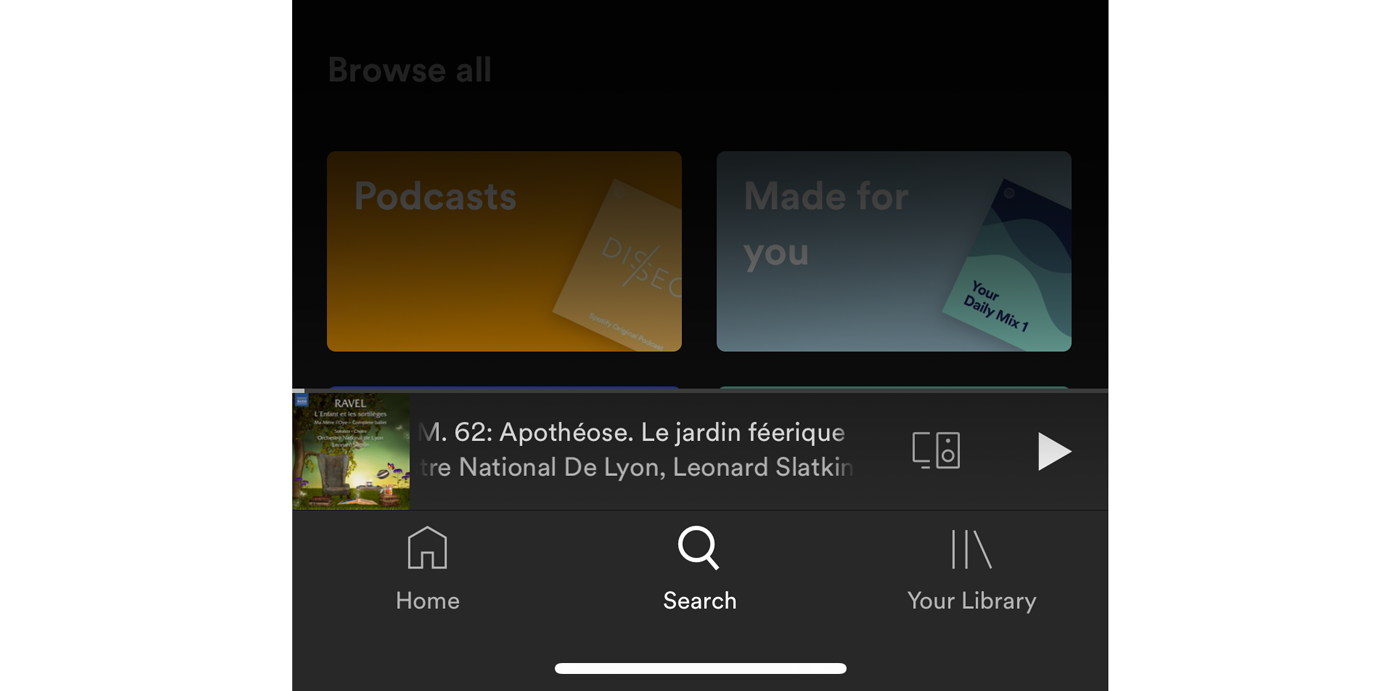

How do you sell a puppy?

Not by talking about how cute, playful or loving it is. You just put it into the customer’s hands, stand back and it sells itself.

A good car salesperson knows when their customer’s ready to buy. They don’t pitch harder at this point, reminding them how beautiful a car is, or how cool they’ll look driving it, or what a great deal this is. They let the customer take it for a spin. They give you as much time as you need to circle the car, sit in it and imagine yourself cruising down the highway with the top down.

A good retail employee knows following you around the store will just scare you away. Instead, they make their presence known. If you have a question, they're ready to answer it. If you need another size, they'll fetch it. When you emerge from the dressing room, they tell you how great you look. When you check out, they say you made a good choice. A smart retail employee knows you're already in the store with your wallet. So they let you shop.

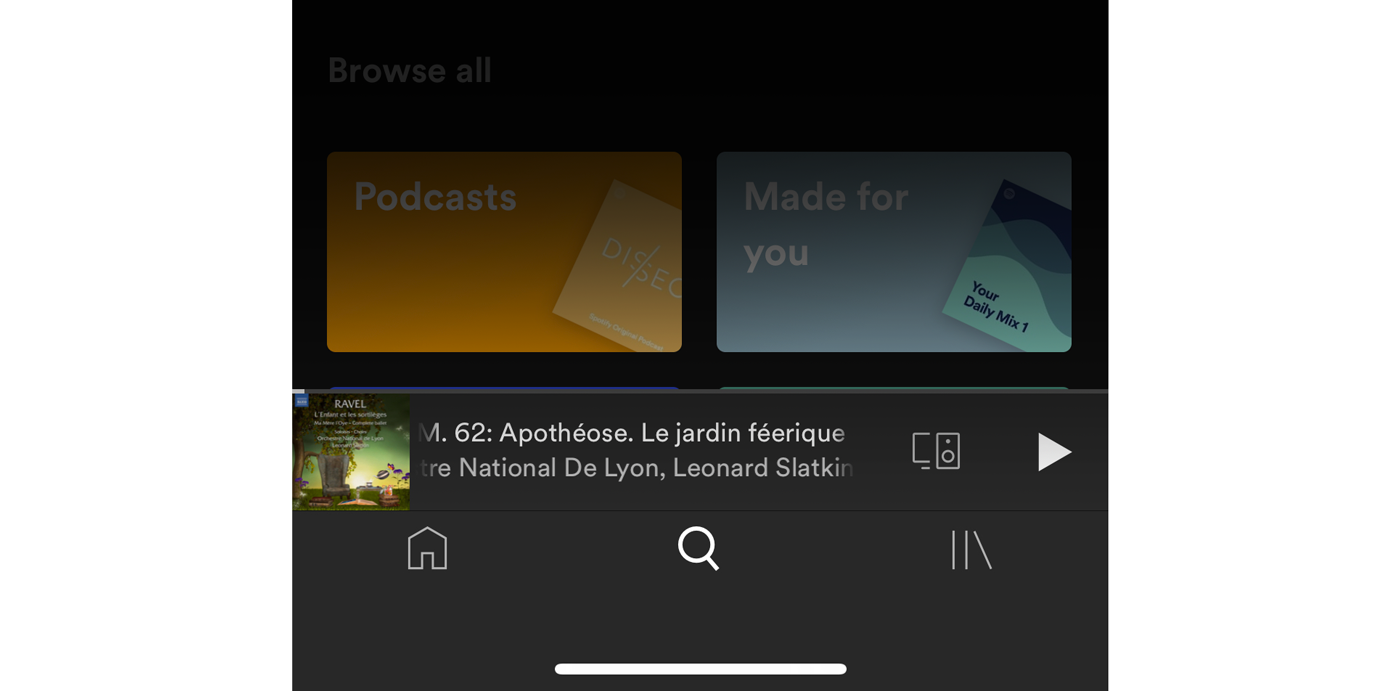

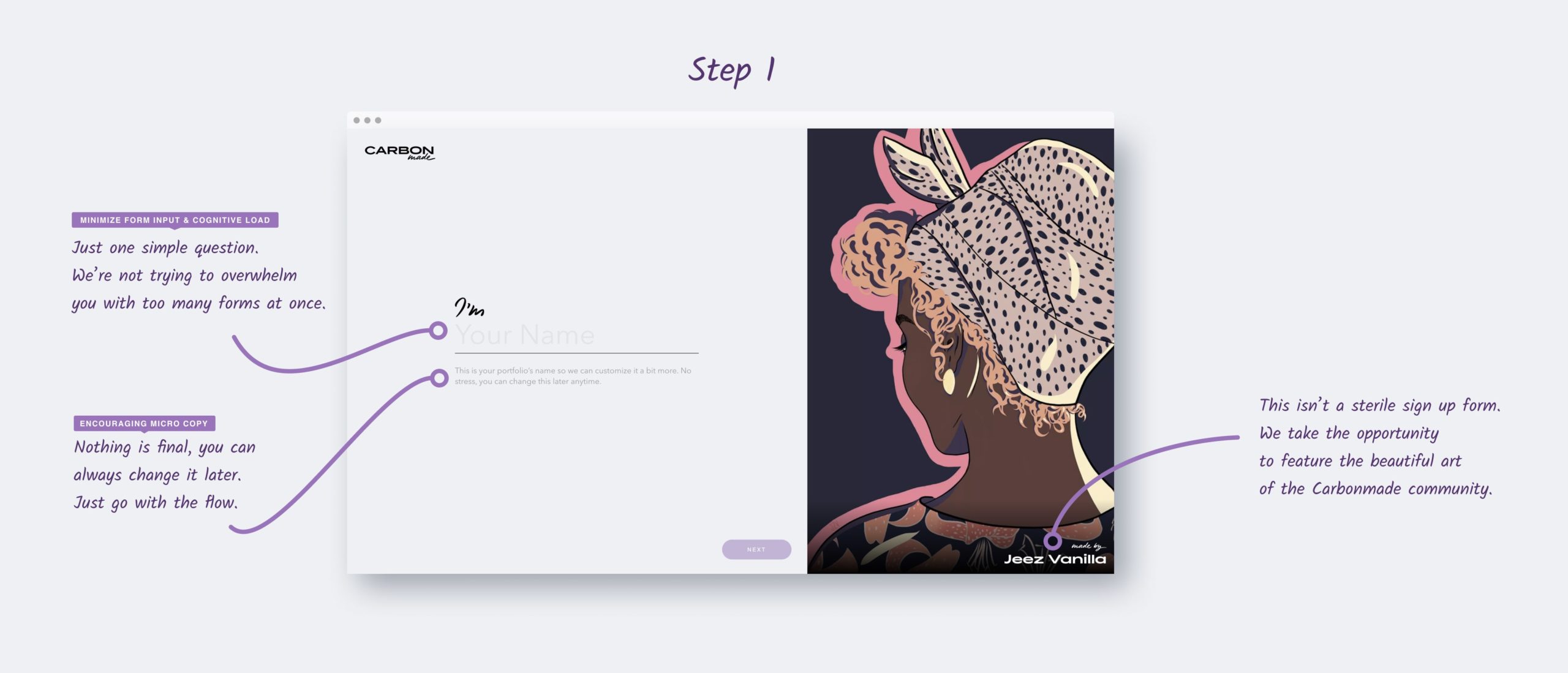

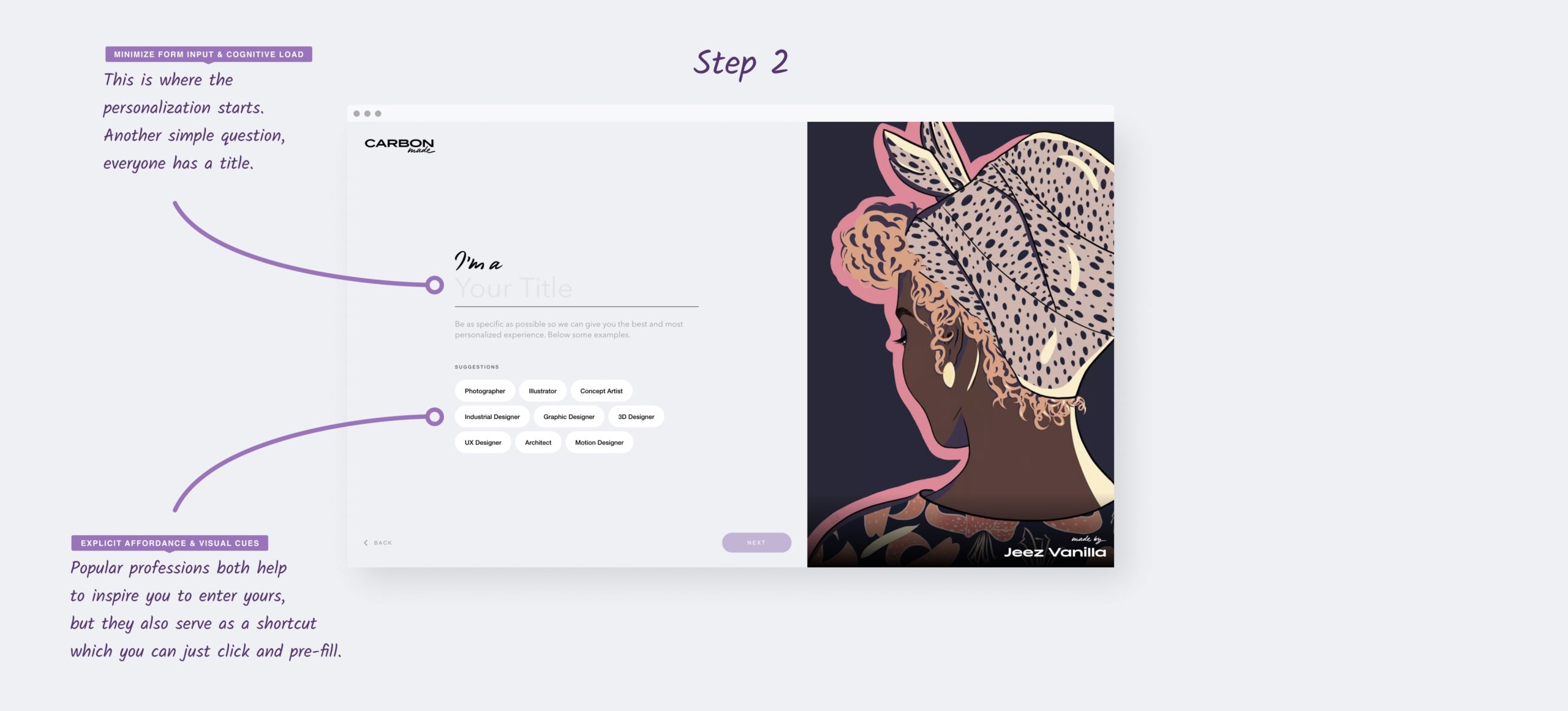

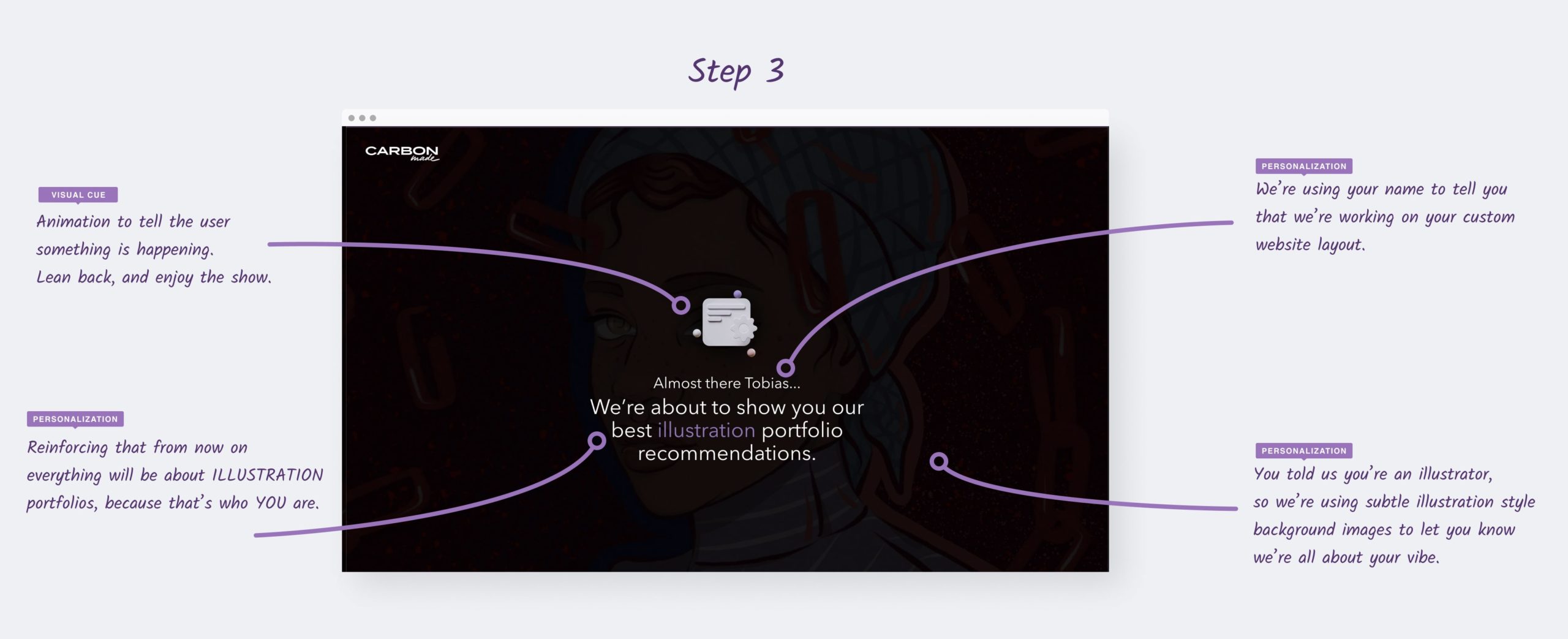

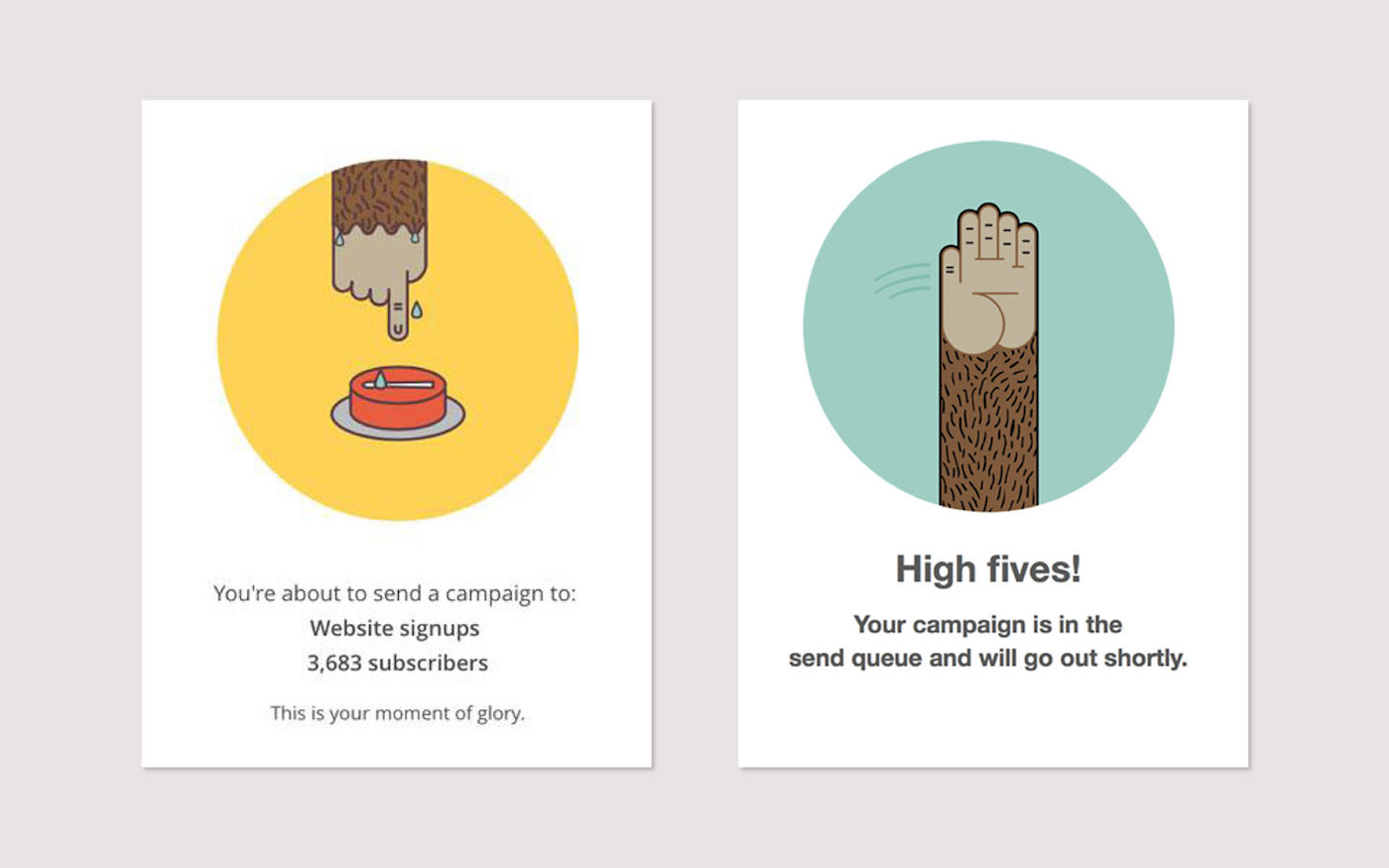

The best products sell themselves too. If someone’s reading your UX copy, that means they’ve already heard your pitch and chosen your product. Now put it in our hands and let us take it from there. Be there if we need you to point us in the right direction. Validate us when we complete a step or make the right decision. Then step back again.

On some occasions, more copy is required to help us understand or appreciate your product. In some cultures, people trust you more when you have more to say. But in most cases, less is better. If you feel like you need to write paragraphs of copy to explain your product, your product may be too complicated. Or you might be trying too hard.

We’re already here. We’re sitting in the car. Let us put the top down and take it for a spin.

Speak to us, not about us.

As Vonnegut said, “Write to please one person. If you open a window and make love to the world, so to speak, your story will get pneumonia.”

We are just one person using your product at any given time. Talk to us, not the room. With that in mind:

This: “The cart is empty”

Becomes this: “Your cart is empty.”

This: “Duplicate song on playlist”

Becomes this: “You already added that song.”

This: “Authorization access denied”

Becomes this: “Ask your admin for access.”

This: “Network connection lost”

Becomes this: “Check your wifi connection.”

We should feel like we’re having a conversation with you as we use your product. Which brings us to our next point.

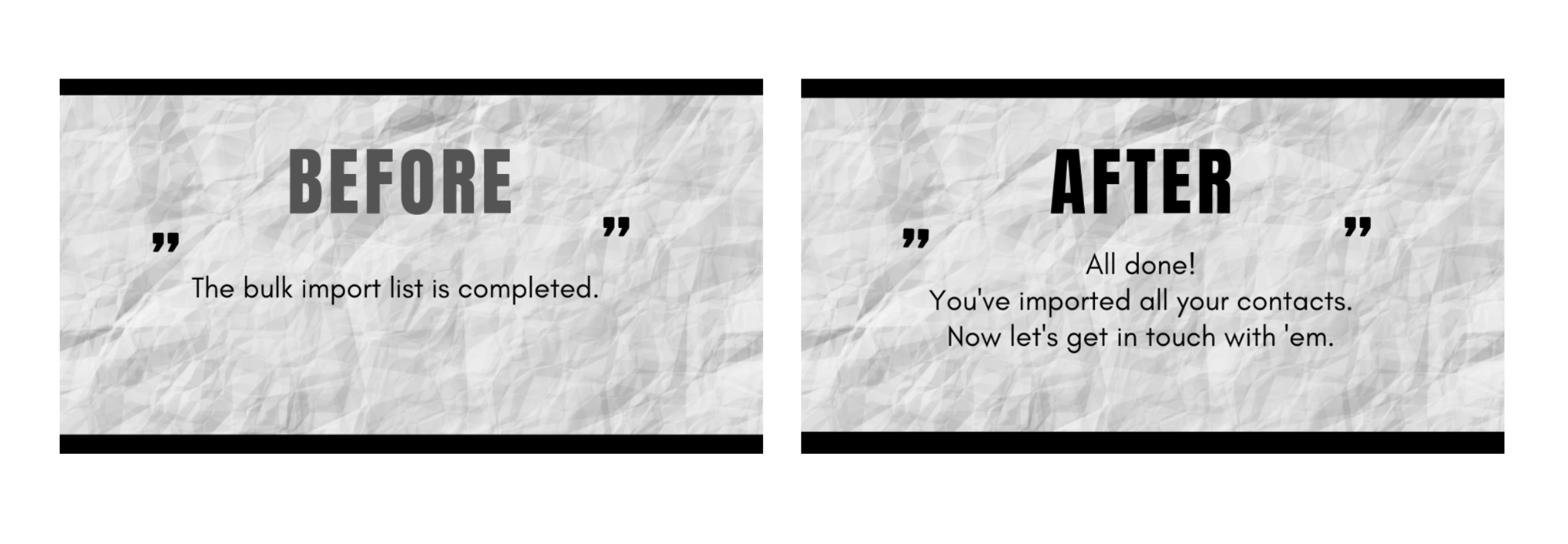

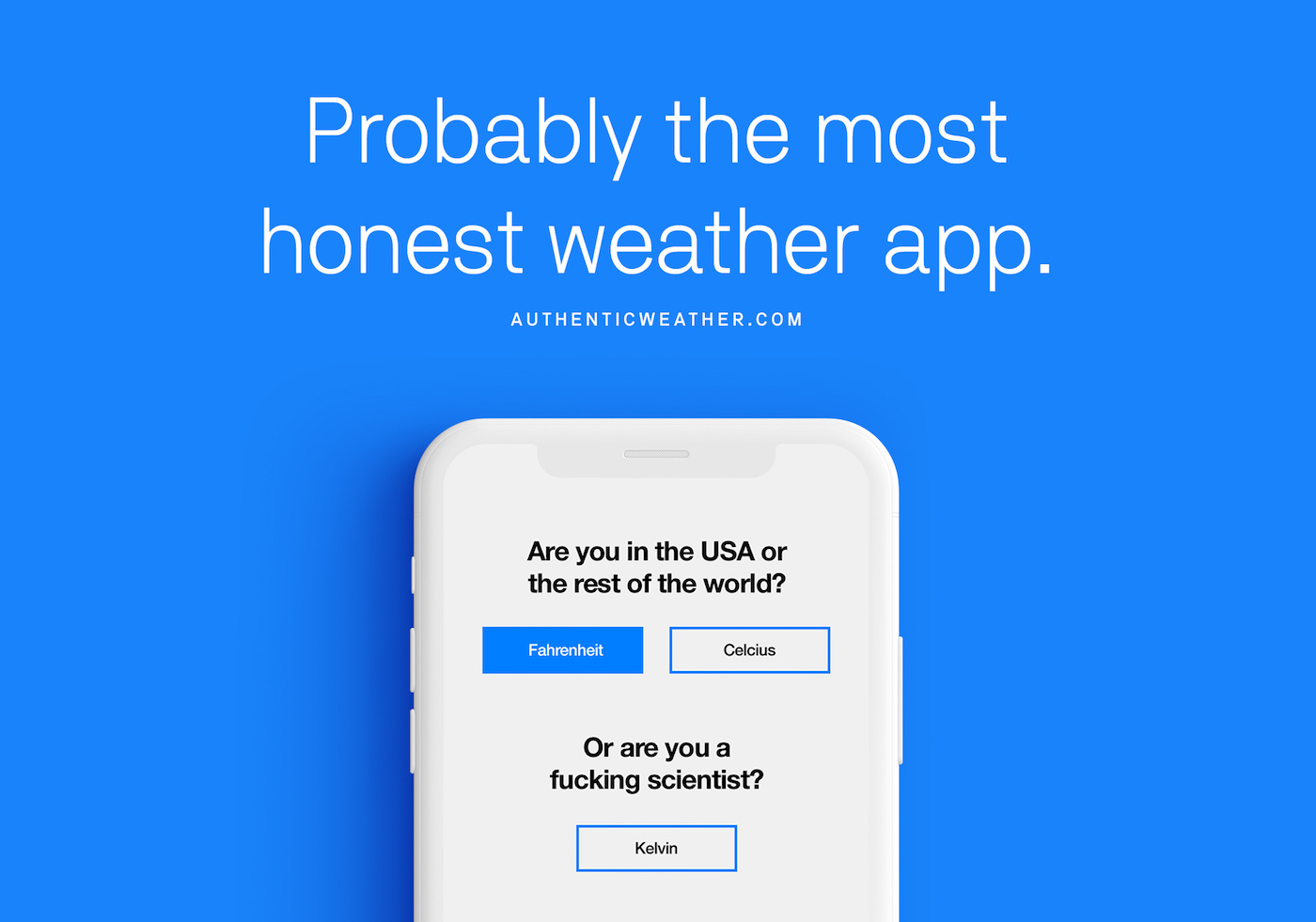

Write like a person, not a robot.

The most loved products feel human. So talk like one:

Don’t be afraid of contractions. We’re used to reading and speaking that way. An error message that reads “You’re not logged in” feels more natural than “You are not logged in.”

Cut the ten-dollar words. Usually, the word that first comes to mind is the right word to use. If you’re looking up synonyms, you’re overthinking it. You wouldn’t say “Please check your inbox for authentication purposes.” You would say “Check your email for the login link.”

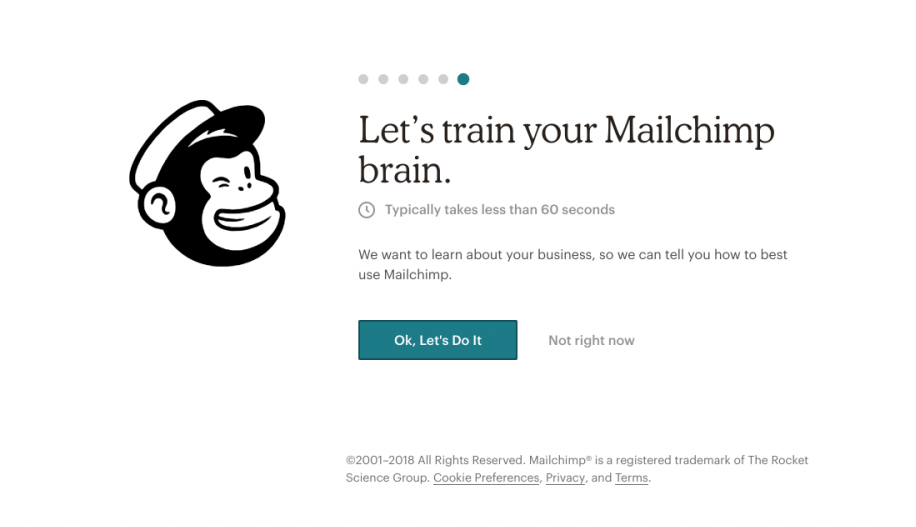

Have a voice. Read through your text messages from your mother, your significant other, your best friend, your boss. They all write differently. They choose different words. They use punctuation differently. You can hear how they sound in your head, based on their unique voice. Your product should have a unique voice too. We talk about how to find your brand voice and apply it to your UX writing here.

When in doubt, read your writing out loud. Does it feel natural to say? Or does it sound stiff and awkward?

Write like you talk. It's not only easier to understand, it's more warm and personal. It's human.

Write for an international audience

Your sentence may feel natural to you, but does it to someone who speaks German as a first language?

Will that 80s American film reference make sense to someone who lives in Singapore?

Will that expression translate to something offensive in Japanese?

Will that sentence fit on a button when written in Mandarin?

Write your UX copy assuming it will be translated. Whether you have an international audience or not, it will make you a better writer.

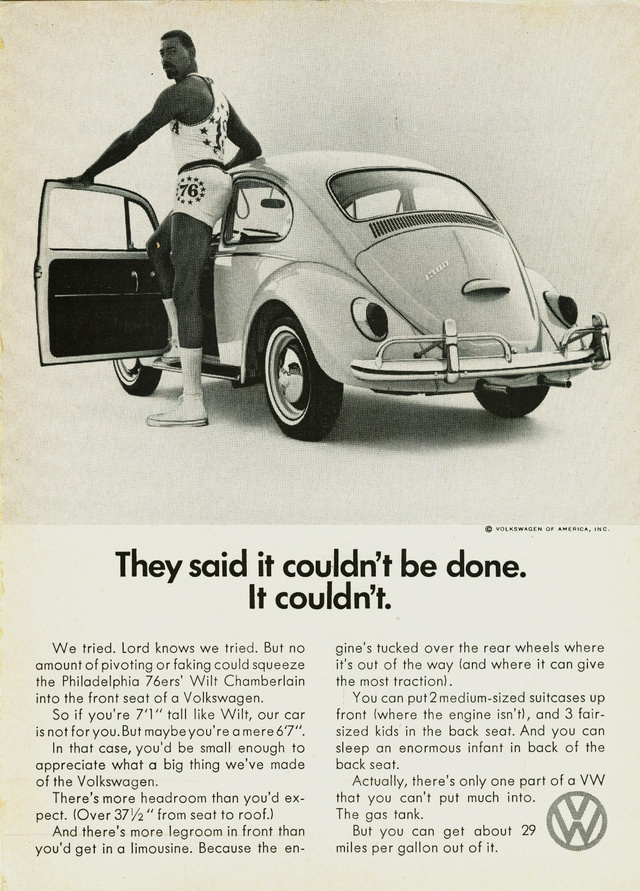

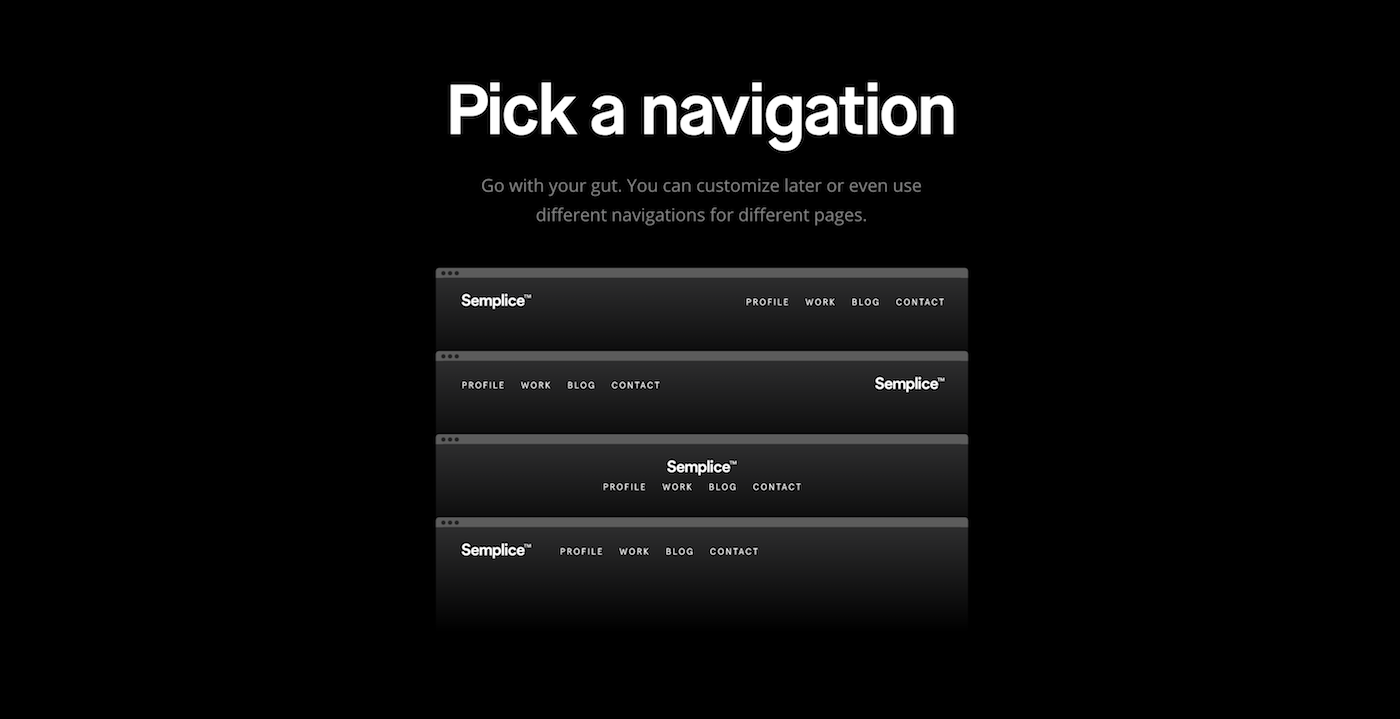

We have people using Semplice.com across the world, and it forces us to write without leaning on puns, references, slang or cliches. We use simple words, not fancy synonyms. We strive to be plain, not poetic. We do the same for our international audience here on DESK.

Read anything by Ernest Hemingway or John Steinbeck and you’ll see simple writing is powerful writing. When you’re not hiding behind stuffy vocabulary, every word rings clear.

Avoid cliches and hyperbole

The only brands who can say they’re “the best” are those that have an award or research to back it up. Otherwise, you’re not saying much at all.

The same goes for cliches like “unleash your creativity” and “optimize your workflow.” We’ve heard it all before. It doesn’t tell us anything useful or different.

The same goes for adverbs. Words like “effortlessly” and “seamlessly” require too much effort to write and are not seamless to read.

The same goes for adjectives. Cut phrases like “award-winning” and “life changing” and you’ll save room, and say more.

Same goes for "faster," "better," "bigger," "smaller," and “more."

These claims and phrases got old and died about 20 years ago. At best, we read right over them. At worst, they make us cringe. And when it comes to UX copy, they just take up precious space.

“Poor Faulkner. Does he really think big emotions come from big words? He thinks I don’t know the ten-dollar words. I know them all right. But there are older and simpler and better words, and those are the ones I use.”

Ernest Hemingway

Keep your sentences short.

Read this sentence from Hemingway’s “The Old Man and the Sea":

“Every day is a new day. It is better to be lucky. But I would rather be exact. Then when luck comes you are ready.”

Now read this sentence from Henry James’ “The Golden Bowl”:

“She had got up with these last words; she stood there before him with that particular suggestion in her aspect to which even the long habit of their life together had not closed his sense, kept sharp, year after year, by the collation of types and signs, the comparison of fine object with fine object, of one degree of finish, of one form of the exquisite with another–the appearance of some slight, slim draped “antique” of Vatican or Capitoline halls, late and refined, rare as a note and immortal as a link, set in motion by the miraculous infusion of a modern impulse and yet, for all the sudden freedom of folds and footsteps forsaken after centuries by their pedestal, keeping still the quality, the perfect felicity, of the statue; the blurred, absent eyes, the smoothed, elegant, nameless head, the impersonal flit of a creature lost in an alien age and passing as an image in worn relief round and round a precious vase.”

Did you actually read that last one? Or did you get turned around and lost halfway through? Me too.

There are times for long sentences, especially in narrative-based writing, where you’re taking the reader on a journey, creating a rhythm and flow. But for UX writing, shorter is better. Use more periods. Use fewer commas.

It’s not about you. It’s about us.

We’re not interested in how hard you worked on your product. Or how advanced the technology is. Or how smart or fast or efficient the system is. We’re interested in what that means for us. How it makes our lives better, makes us look better, makes thing easier or otherwise benefits us.

You could talk about the better camera lens. Or you could talk about the sharper, higher quality photos we can take.

You could explain the layers of security in your highly encrypted checkout. Or you could tell us our information will be safe.

You could say you’ve been awarded for your fast delivery times. Or you could say we’ll receive our food in an hour, guaranteed.

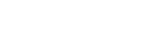

Make it scannable

Want us to read your copy?

Then let us skim it.

___

Read more from our UX copywriting series:

→ Content or design first?

→ Best practices for UX copywriting

→ We don't want to read your UX writing

→ My best products are a joke

→ Writing UX copy for buttons and links

→ Making your product a joy to use

→ What is UX copy?