An emotional tech product is a lifestyle product. It doesn’t necessarily solve a problem. It’s there for entertainment. It’s not a product that people need, it’s a product they choose. Think Netflix, TikTok or Instagram.

A utility product is a service. It exists simply to fill a need, improve a process or connect one thing to another. It’s meant to be used, not necessarily enjoyed. You want to be in and out, quickly. Examples: Google Docs, your banking app, your weather app.

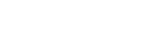

More and more lately, the lines between the two are blurring. Utility apps are marketing themselves the way emotional apps do. They are appealing to our personal values and emotions rather than simply offering solutions to a problem. They are attempting to build a community around their product. They promise their product is more than just the service they provide. It’s a lifestyle.

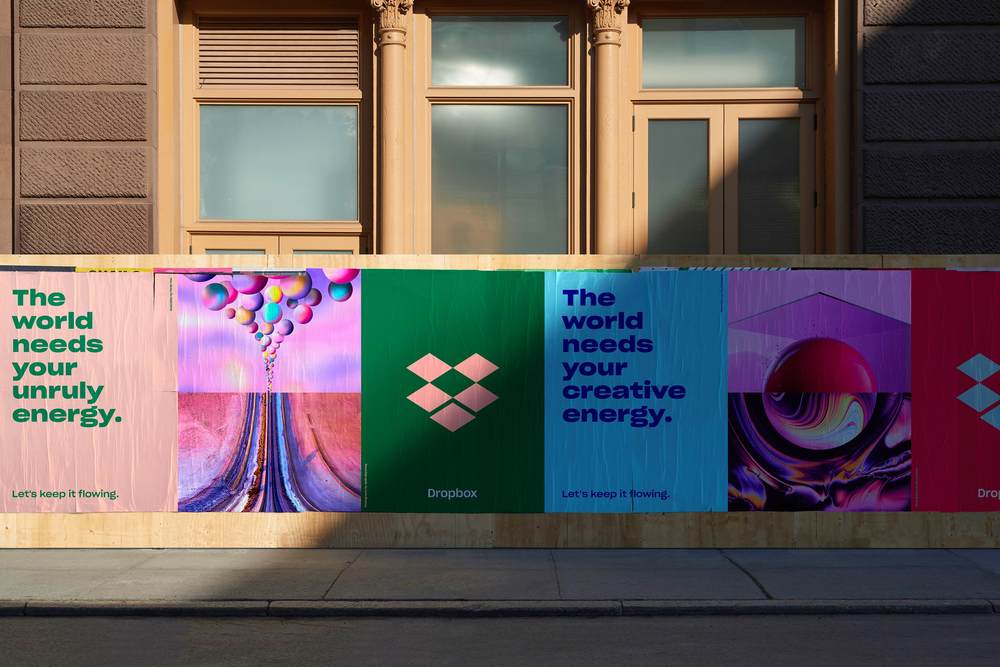

Take the 2017 Dropbox redesign, for example.

The new Dropbox logo was released with lines like “Making the everyday more extraordinary” and “unlocking creativity.” Vibrant ads started popping up around Brooklyn, joining the likes of whiskey and Adidas billboards, with headlines like “the world needs your dreamy energy.”

The redesign was a departure from the tech company look; it was aesthetically pleasing. It felt fresh and modern, which is essential as times and styles change. But while Dropbox has expanded into creation tools like “Paper,” I still consider it a utility product. At the end of the day, most of us simply use Dropbox to store and organize files. I don’t *love* Dropbox, but I use it. And that’s okay. We don’t want it or need it to be more than that.

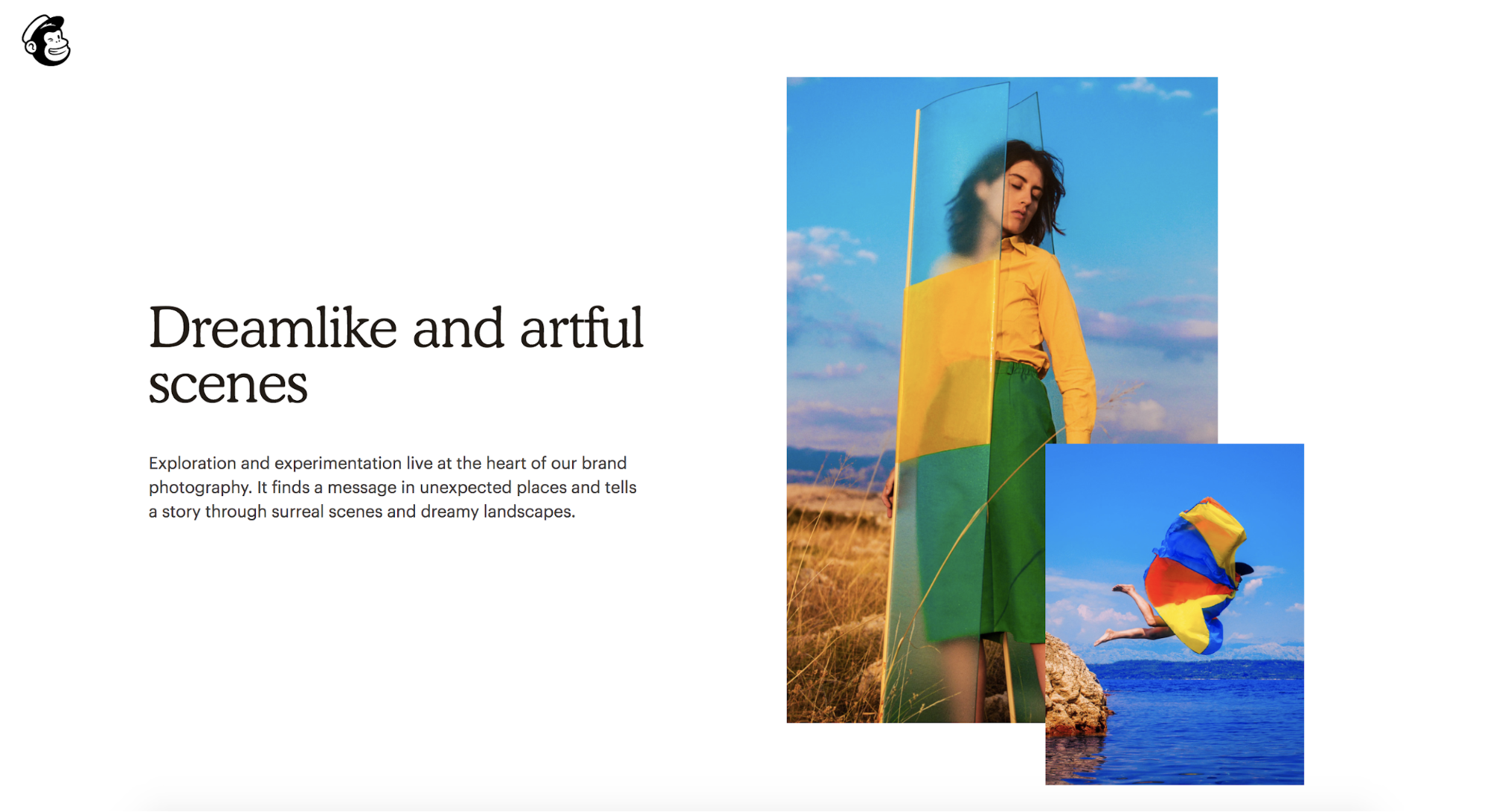

Or consider the Mailchimp redesign from 2018. While many creative folks use Mailchimp, it is ultimately a tool for creating emails and marketing campaigns. It’s a means to an end, not the end itself. It’s the medium, not the message. Yet the new brand uses whimsical illustrations and “artful scenes” to present its offering. Again, we see a utility product marketing itself as an emotional product.

Of course, it makes sense that a brand would play on emotions to sell their product. It’s not sneaky or misleading. A brand wants to connect with people, and people are emotional beings.

When you set out to buy a hammer, you’re not necessarily looking for a community, or a hammer “that’s more than a hammer.” You just need to nail something, and this is the tool to do it. You would likely choose the first solid-looking, affordable hammer you set eyes on.

But what if you learned that your grandfather swore by a specific hammer that hangs in his toolshed to this day? Or that this hammer has been used for over a century by the proud working class? What if I said this specific hammer enables creativity? That it’s the centerpiece of a sculptor’s or artist’s profession? I could go so far as to say this hammer allows art and creativity to exist. So do email clients and online file storage.

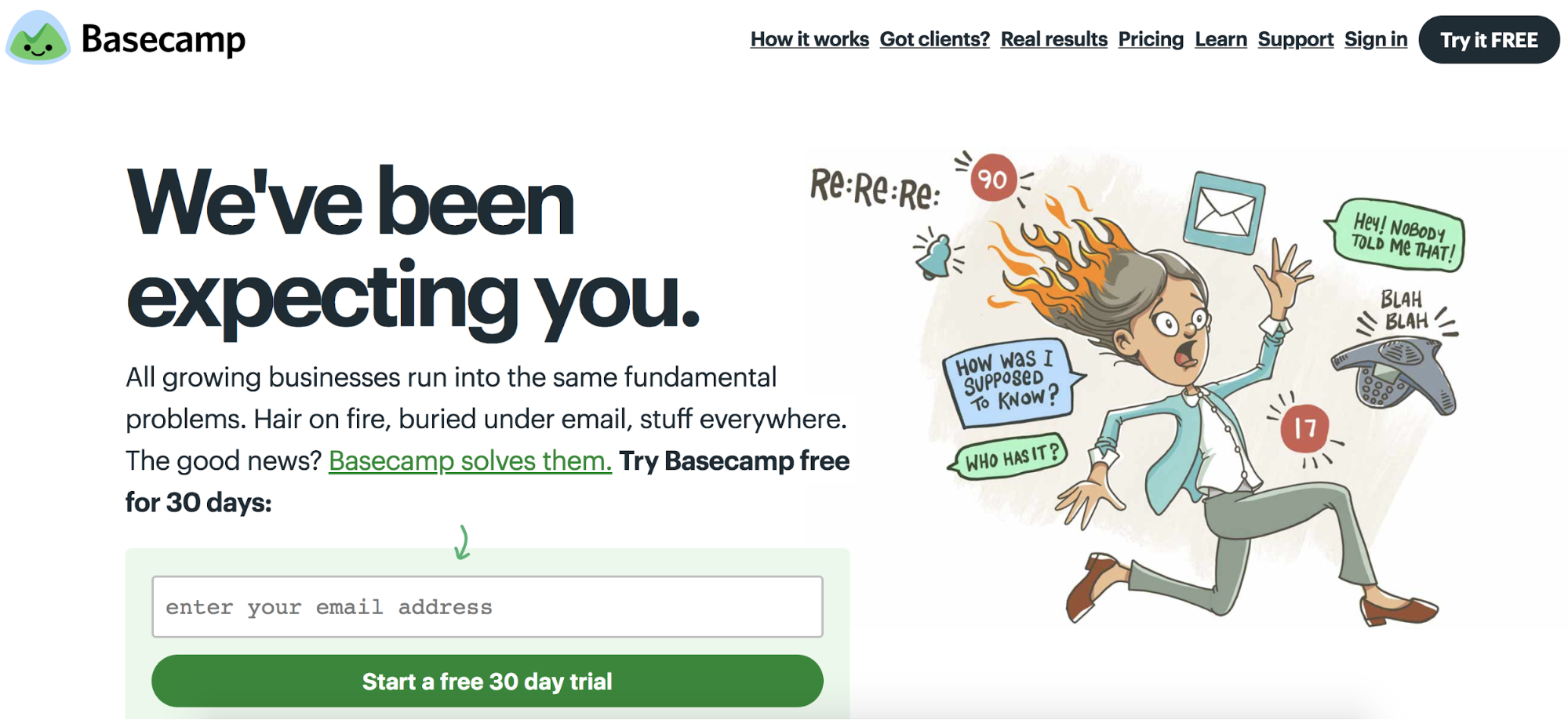

But let’s look at the other side. Two companies that are non-emotional, utility tech products and own it: Slack and Basecamp. These companies also use playful imagery, but their message is straightforward. Slack is where work happens. Basecamp solves the fundamental problems of growing businesses. Both of these brands offer a tool, and that tool does their job well. That’s it.

Maybe it’s enough for a product to be functional.

Last year or so, Slack redesigned its logo. Naturally, the design community was is an uproar. They Tweeted about the logo and Slacked the Slack logo to each other on Slack asking for everyone’s opinion and the only one I had was: Why does it matter?

People use Slack because it’s faster and easier. I like the logo and I generally enjoy the way Slack works, but I don’t love it like I love my favorite sweater. If something comes along that’s better, I will use that. It’s a utility. Nothing more, nothing less.

Slack is not Nike. The app’s design is pleasing and modern, but I don’t choose Slack because it inspires me or aligns with my values. And that’s OK. I understand that some people feel differently or have a more emotional connection to Slack, but I’d guess that most use Slack because their company uses it, and because it just works.

Yes, brands exist that offer both emotion and utility. Apple is an obvious example. Apple was at the forefront of this marketing approach, and they’ve always done it well. Apple products were never just computers or smartphones, they were tools that enable creativity. Before Apple entered the mainstream, it focused heavily on the creative class. Everyone knew that if they want to be taken seriously as a designer or filmmaker, they better use an Apple product. Apple computers are a tool that became a lifestyle, even a cult. So it is possible for a product to successfully do both.

Maybe it’s companies like Apple that have inspired this wave of emotional marketing for utility products. Or maybe, perhaps through social media, we as consumers are signaling that this is what we want from a product. Or maybe the agencies for these brands are pushing trendy strategies like content marketing as a one-size-fits-all marketing plan.

The approach can clearly work. But as more and more brands get on board, I start to question it. Does every utility brand need to market themselves as a lifestyle brand to succeed now? Or is it enough to simply provide a great product that solves a problem? Utility brands can have personality, but is it accurate to market a time-tracking app or note-taking tool like a Coca Cola commercial? Do I now need to politically align with my note-taking app? Does my hammer need to encourage freedom and creativity? Or can it just be a hammer?

In this quest to connect with consumers on an emotional level, are we sacrificing clarity and honesty? Will it all start to feel contrived, confusing and trite?

Perhaps tech companies need to be more realistic about who they are as a brand and what they actually offer to consumers. Maybe, as utility brands, they should be more focused on delivering value through functionality, utility, privacy and discretion, rather than promoting lifestyle values.

Maybe a good tool doesn’t need to inspire. Maybe a tool that works well, speaks for itself.

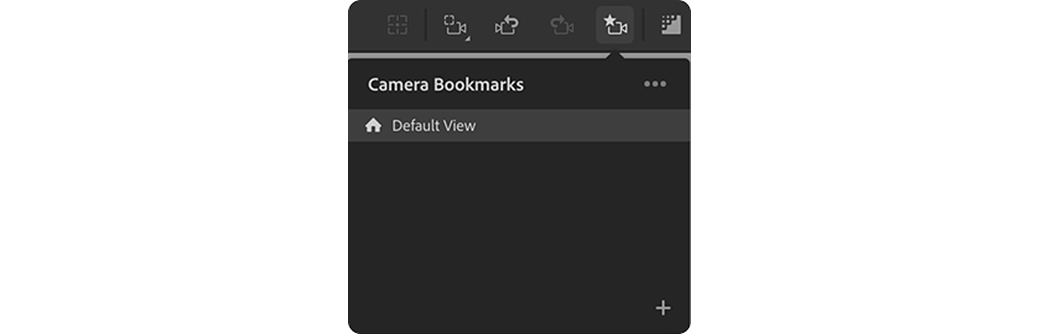

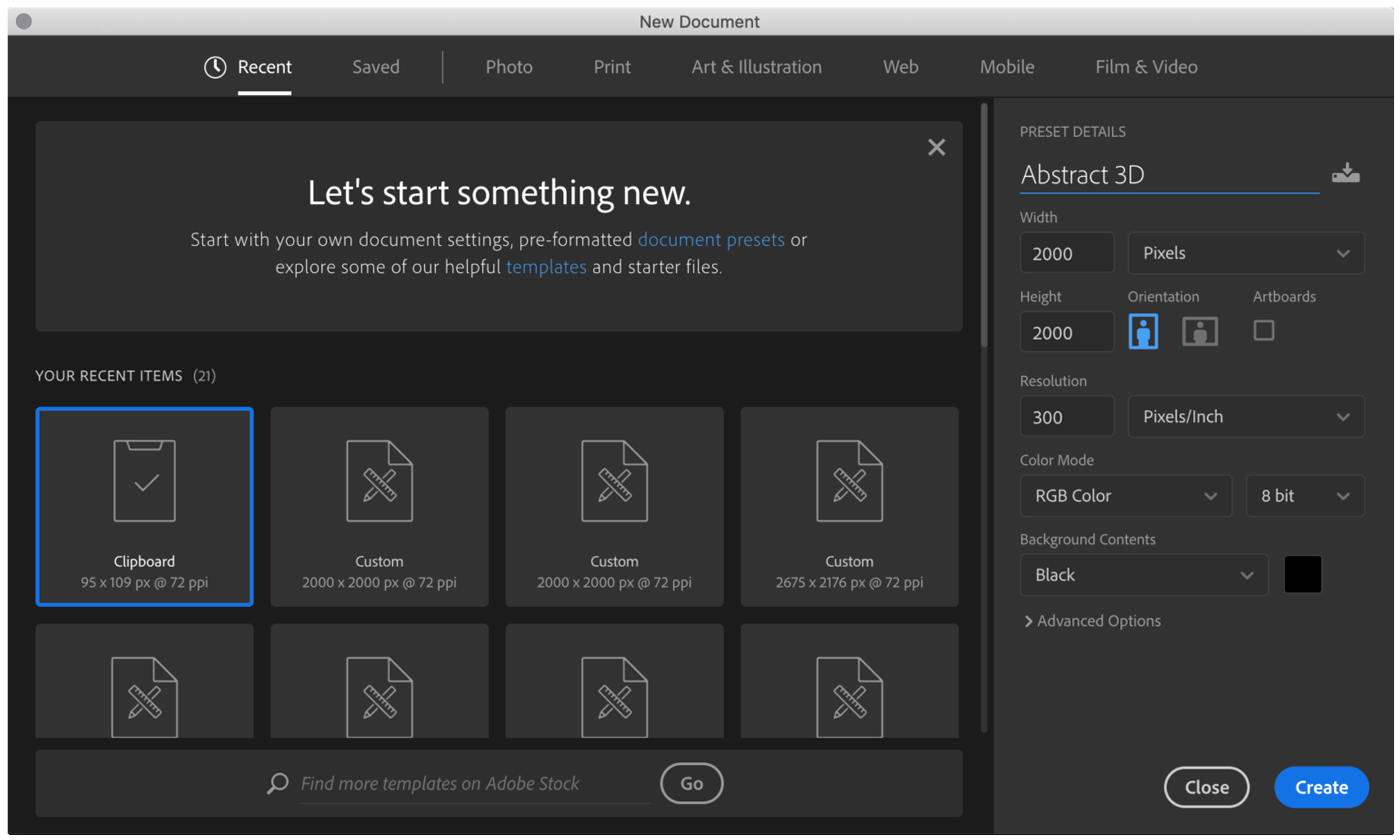

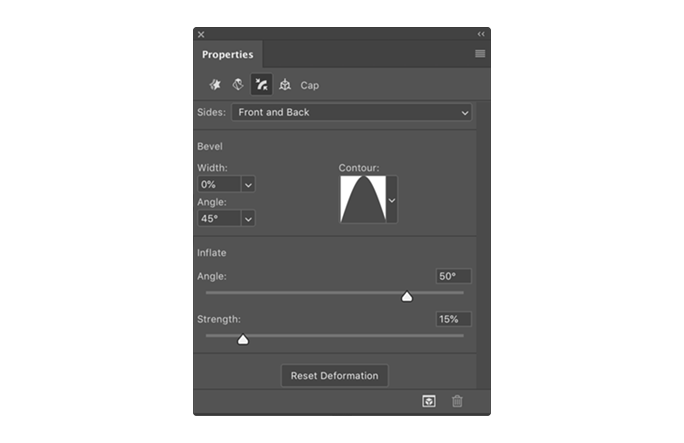

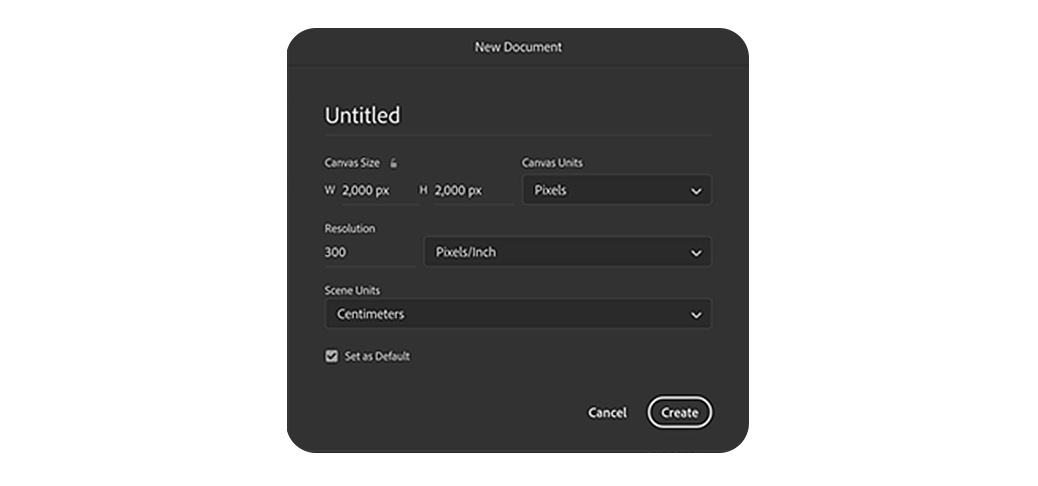

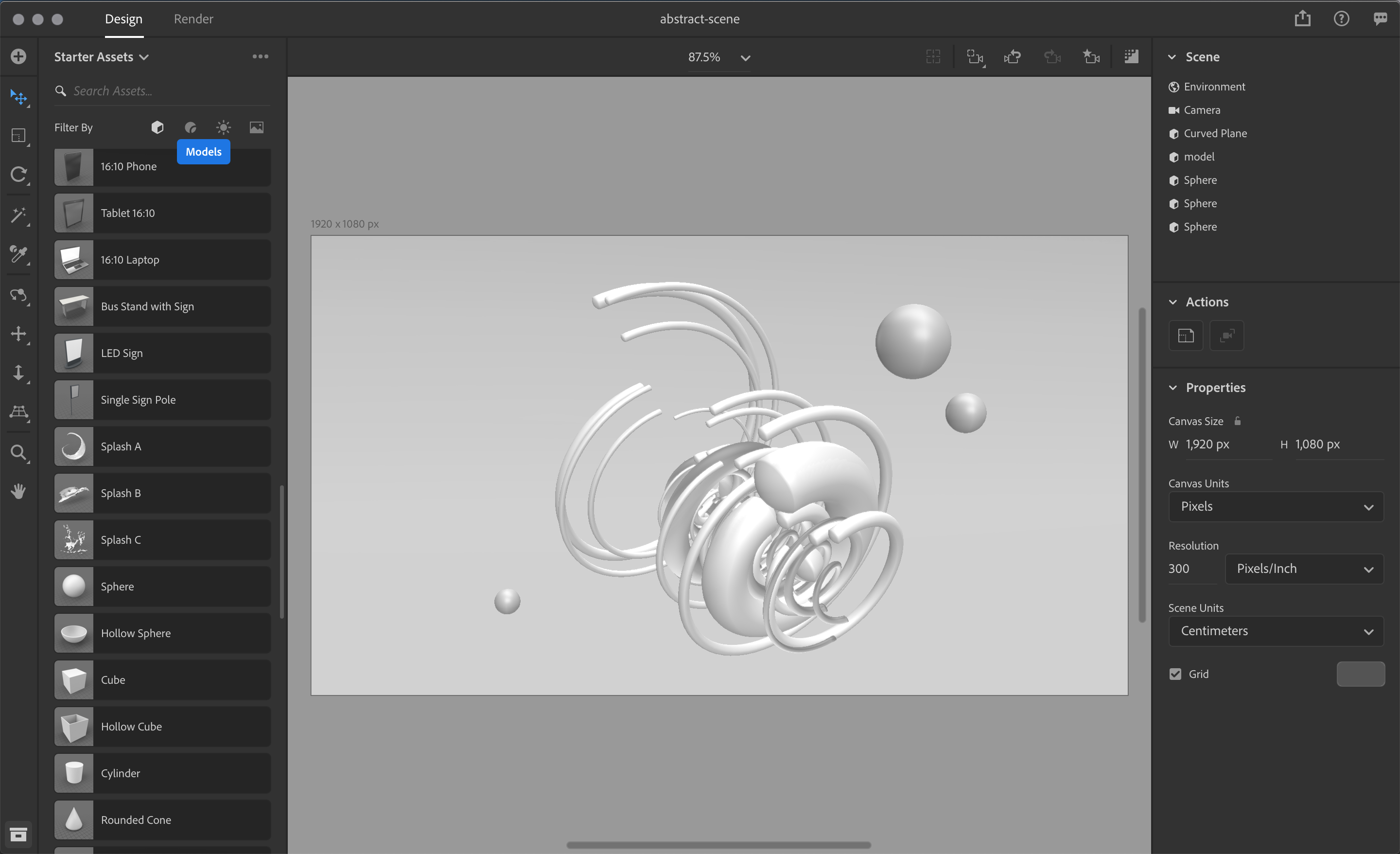

Step 8: Setting our camera

Step 8: Setting our camera